Stone Sentinels of Power: The Lamassu of Persepolis

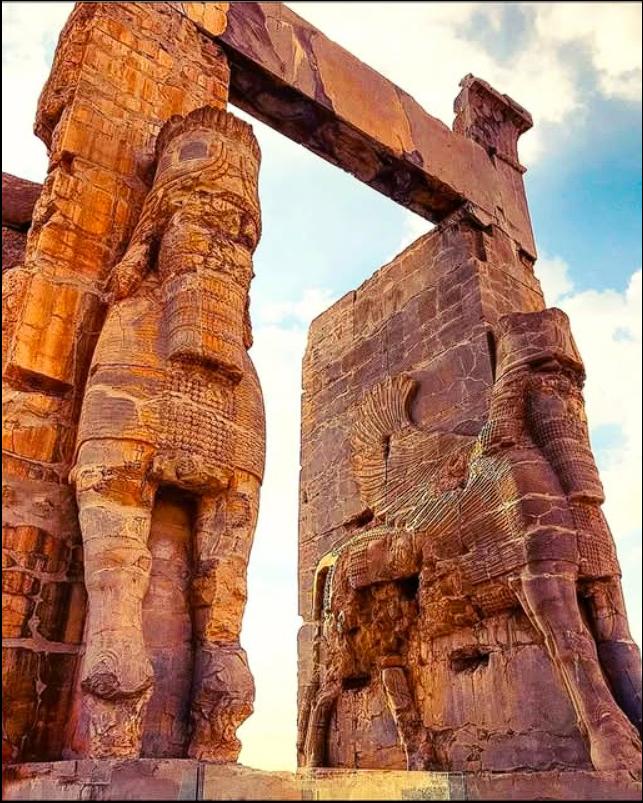

Perched at the ceremonial threshold of Persepolis, the once-glorious capital of the Achaemenid Empire, the Lamassu statues—majestic winged bulls with human faces—stand as enduring symbols of an ancient civilization’s grandeur. Commissioned by King Xerxes I in the 5th century BCE, these monumental sculptures were more than artistic marvels. They were guardians, spiritual emissaries, and royal declarations of strength, intelligence, and divinity.

Origins and Historical Context

The Achaemenid Empire, founded by Cyrus the Great and reaching its zenith under Darius I and Xerxes I, stretched from the Indus Valley to the Aegean Sea. As a showpiece of this vast empire, Persepolis was constructed not merely as a city but as a ceremonial capital meant to impress visiting dignitaries. One of its most iconic entrances, the Gate of All Nations, was designed to project imperial might and multicultural unity.

It was at this grand portal that Xerxes I ordered the installation of two colossal Lamassu figures. Inspired by earlier Mesopotamian traditions, these hybrid creatures had already served similar functions in Assyrian and Babylonian palaces. However, their incorporation into Achaemenid architecture marked a unique cultural fusion and a new chapter in their symbolic use.

Anatomy of the Lamassu: Symbolism in Form

Each Lamassu is a synthesis of multiple beings:

Bull’s body: Representing brute strength, fertility, and stamina—qualities highly prized by the Persians in leadership and governance.

Human head: Adorned with a dignified beard and headdress, this element suggests wisdom, rational thought, and royal authority.

Wings of an eagle: Signifying divinity, speed, and a connection to the celestial realm, emphasizing the king’s mandate from the gods.

Together, these attributes reflected the ideal ruler—one whose governance was balanced by power, intelligence, and divine approval.

Furthermore, their imposing scale—several meters tall and carved from single, massive stone blocks—was a calculated architectural decision. They were not merely statues but stone titans, whose towering presence would awe any entrant, silently warning: this was the seat of an empire blessed by Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity in Zoroastrianism.

Craftsmanship and Construction

.jpg/960px-thumbnail.jpg)

Creating a Lamassu required not only artistic mastery but also logistical prowess. The stone used for the statues at Persepolis was quarried locally and transported with immense effort. Artisans meticulously carved the hybrid figures, giving delicate attention to facial features, the feathers of the wings, the curled tufts of the beard, and the muscles of the bull’s haunches.

Unlike the Assyrian versions, which often had five legs to appear properly proportioned from both front and side views, the Lamassu of Persepolis exhibit a more frontal, imposing stance, emphasizing gatekeeping over illusionary realism.

Their construction wasn’t just a feat of technical ability; it was an expression of the empire’s access to skilled labor, material resources, and centralized authority. Every chisel mark echoed the strength of an empire that could summon thousands to work in harmony for a single monumental purpose.

The Gate of All Nations: A Threshold of Diplomacy

The Gate of All Nations itself was a massive audience hall flanked by these Lamassu figures. Inscriptions in Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian, and Akkadian languages attest to the multicultural reach of the Achaemenid Empire, whose provinces included people from all over the ancient world—Medes, Egyptians, Greeks, Babylonians, and Scythians among them.

As foreign envoys approached, they would pass beneath the watchful eyes of these silent stone guardians. This was intentional. The Lamassu weren’t simply decorative; they functioned as psychological deterrents and diplomatic symbols. They conveyed a dual message: hospitality and dominance. “You are welcome,” they seemed to say, “but never forget whose realm you enter.”

Spiritual Guardians and Apotropaic Force

Beyond political symbolism, the Lamassu carried spiritual weight. Rooted in ancient Mesopotamian religious beliefs, these beings were considered apotropaic—possessing the power to ward off evil and misfortune. Their placement at gateways, both secular and sacred, was intended to create a divine threshold between the profane outer world and the sanctified inner court of the king.

In Zoroastrian belief, the world was a battleground between good (Ahura Mazda) and evil (Angra Mainyu). The Lamassu, as protectors, served as stone expressions of divine order guarding against chaos. Their silent vigilance contributed to the sanctity of Persepolis as a cosmic center of harmony and governance.

Legacy and Preservation

The Lamassu of Persepolis survived the ravages of time, invasions, and weathering far better than many other structures. Even when Alexander the Great sacked Persepolis in 330 BCE—setting fire to the great audience hall of Xerxes—they remained standing, grim survivors of imperial collapse.

Today, they continue to fascinate historians, archaeologists, and travelers. Unlike their counterparts in Mesopotamian museums or those plundered and sold to collectors, the Persepolitan Lamassu remain in situ, evoking the exact spatial and cultural awe they were designed to instill.

Efforts by Iran’s Cultural Heritage Organization and international archaeological collaborations have helped preserve and document these masterpieces. Through 3D scanning, digital modeling, and conservation efforts, the Lamassu have found renewed relevance in modern scholarship.

Modern Resonance: A Message Across Time

Standing beneath the Lamassu today, amidst the silent ruins of Persepolis, one cannot help but feel the weight of history. These are not mere relics—they are narrators in stone, retelling the story of a civilization that once envisioned itself as the axis of the known world.

In an age of shifting borders and cultural fragmentation, the Lamassu remind us of a time when empires aspired not only to rule, but to embody ideals of strength, wisdom, and divine justice. Their endurance is a testament to the power of symbols and the human desire to leave behind sentinels that speak beyond language, across millennia.

Conclusion

The Lamassu of Persepolis are more than mythological hybrids or architectural ornaments. They are the embodiment of an empire’s identity—simultaneously spiritual guardians, political declarations, and artistic triumphs. In their gaze, frozen in stone but alive with meaning, we glimpse the eternal desire of civilizations to guard their values and project their visions into the future. As long as they stand, they will continue to speak—not with voices, but with presence.

News

Incredible Twist: K9 Dog Goes Into Overdrive, Barking Non-Stop at Woman with Baby—When the Truth Behind the Dog’s Actions Was Revealed, the Entire Airport Terminal Was Left Reeling. The Startling Reason Behind the Dog’s Behavior Will Have You on the Edge of Your Seat.

The Unseen Guardian: How a K-9 Dog Prevented a Child’s Abduction In the midst of a routine day at Gallatin…

Devastating Truth Revealed: The Dog’s Hunger Was Overwhelming, Yet He Refused to Eat. The Vet’s Stunning Discovery Behind This Heartbreaking Behavior Will Leave You Speechless—A Tale of Survival and Unimaginable Pain That Will Tuck Deep Into Your Soul.

“Leo’s Story: A Journey of Survival, Redemption, and the Unbreakable Bond of Love” In a small, quiet clinic nestled in…

“Sheriff and K9s Risk Their Lives to Save Abandoned Baby — What They Uncover Next Is Unthinkable and Will Shatter Your Soul!”

“The Silent Heroes: The Remarkable Story of Loyalty, Love, and the Unbreakable Bond Between a Police Chief and His K9s”…

In a Shocking Turn of Events, a German Shepherd Becomes the Hero After a Deadly Car Crash—The Sheriff Was Supposed to Die, But This Brave Dog Defied All Expectations, Changing His Life Forever. Find Out How This Incredible Rescue Unfolds in a Way You Won’t Believe!

Max the German Shepherd: The Guardian Who Saved a Town It was a cold, stormy night when Ashwood Ridge’s Police…

Unbelievable Discovery at Kennel 12: Dog’s Heartbreaking Cries Lead Vet to a Jaw-Dropping Revelation—What Was Found Inside Will Shock You to the Core! The Mysterious Secret of Animal Shelters Exposed in a Way No One Expected. Prepare to Be Stunned by What Happens Next!

A Golden Rescue: The Story of Marley and Elise In the small town of Willow Creek, nestled between snow-dusted hills…

Unbelievable Moment: Officer Breaks Down in Tears Beside His K9’s Coffin—Then One Single Bark Pierced the Silence, Leading to the Most Shocking Twist of Justice! What Happened Next Will Leave You Breathless and Restore Your Faith in Loyalty, Justice, and Unbreakable Bonds Between Officers and Their K9 Partners.

A Hero’s Legacy: The Silent Bark that Uncovered Justice and Changed Lives Forever Red Hollow, Colorado, sat quietly beneath the…

End of content

No more pages to load