What Lies Beneath the Black Sea? The 2,000-Year-Old Shipwrecks That Changed History

At first glance, the Black Sea appears tranquil, even benign. But beneath its glassy surface lies one of the most extraordinary underwater graveyards in human history—an oxygen-deprived abyss where time stands still, and where wooden ships that sailed thousands of years ago rest almost perfectly preserved. Now, for the first time, we are beginning to truly understand the stories they have to tell.

For maritime archaeologist John Adams and his team, the Black Sea is not just a body of water—it’s a portal into the past. With funding exceeding $20 million and some of the most advanced undersea equipment ever deployed, Adams embarked on a three-year mission to uncover the sunken secrets of this mysterious region. What they discovered was breathtaking.

The expedition’s base, the Stril Explorer, was a 3,000-ton high-tech Scandinavian survey ship originally built to weather the North Sea. Outfitted with state-of-the-art sonar and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), the vessel carried an international team of scientists, engineers, and divers. Their goal: to map the prehistoric seafloor and locate shipwrecks that could date back as far as 3,000 years.

Why the Black Sea? Because unlike most other oceans, where wooden ships quickly decay due to oxygen-rich waters and invasive species like shipworms, the Black Sea becomes an anoxic “dead zone” below 150 meters. No oxygen means no life—and that means no decay. A ship that sank 2,000 years ago can remain on the seafloor looking much as it did the day it disappeared.

Early on, the team located a stunning Ottoman-era wreck from around 300 years ago. Ropes still draped across beams. Ornate Islamic carvings bloomed like flowers along the quarterdeck. It was so well-preserved that some on the team thought it might be a movie prop—until they realized the truth: no one had seen this ship since the day it sank.

But this was just the beginning.

Working in shifts around the clock, the scientists extracted over 70 sediment cores and scanned hundreds of square kilometers of seabed. They weren’t just searching for wrecks—they were also trying to solve a long-standing scientific debate: how did the Black Sea flood? Was it a gradual process over thousands of years? Or was there a cataclysmic deluge that inspired the biblical story of Noah’s Ark?

Their cores showed layered evidence of prehistoric lake sediment slowly overtaken by marine mud—proving that the Black Sea was once a vast freshwater lake, later flooded by the rising Mediterranean over millennia. The Biblical flood theory, they concluded, was myth—not science.

But shipwrecks remained the emotional heart of the expedition.

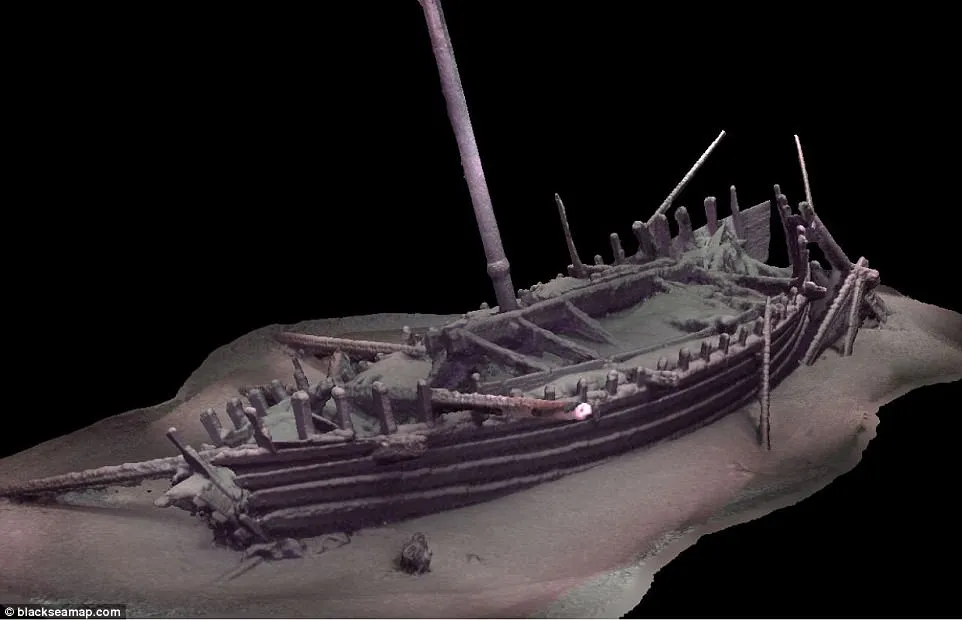

In one of the most intense moments of the journey, the ROV descended over 2 kilometers to inspect a ghostly shape embedded in the deep seabed. As cameras flickered to life, a Greek merchant vessel emerged from the gloom. The rudder, carved with a distinctive curve, matched illustrations from fifth-century BCE pottery—the so-called “Siren Vase.” The ship likely sailed during the lifetime of Plato and Socrates. Its mast still stood. Its hull, quarter rudder, and structure were intact. It was the oldest shipwreck ever found in such pristine condition.

Later, in shallower waters off the Bulgarian coast, another discovery stunned the team: a Roman cargo ship from the first century AD. Amphorae—clay jars used for storing olive oil and wine—were still stacked in the hold, tied together with ancient rope. Some even bore soot marks, as if they had just come off a Roman grill.

Using a modified toilet plunger and suction device rigged to the ROV, the team managed to retrieve one amphora intact. Inside: sediment, soot, and ashes—the last meal of a lost Roman crew. It was a haunting, visceral reminder that shipwrecks are not just artifacts; they are the final chapters in human lives.

Yet not every dive was successful. Many times, the team found “IKEA wrecks”—similar Ottoman vessels, virtually flat-packed by centuries on the seabed. At one point, they nearly lost their ROV to strong currents. At another, they discovered the steel equipment was being eaten away by hydrogen sulfide, a poisonous gas that lurked in the water like a corrosive ghost.

The team also uncovered troubling evidence that even in this perfect environment, bacteria may slowly be devouring the wood from ancient wrecks. While the ships appear intact on video, under a microscope the timber is sponge-like—degraded beyond belief. It was a sobering realization: these relics may not be as immortal as once believed.

Still, by the expedition’s end, Adams and his crew had documented over 60 wrecks—each one a frozen moment in maritime history. From a medieval ship possibly sailed by Marco Polo, to a 2,000-year-old Roman freighter still carrying its cargo, to a Greek merchant ship preserved in uncanny detail, the Black Sea had yielded more than anyone had dared imagine.

In their final days at sea, the scientists realized the scale of what they had only begun to uncover. Thousands of years of trade, conquest, and migration lie beneath this enigmatic sea. Adams put it best: “We’ve only scratched the surface.”

With 3D photogrammetry, underwater drones, and global collaboration, the future of maritime archaeology has arrived. But nothing—not even the most advanced technology—can replace the wonder of looking through a camera lens and seeing a 2,000-year-old rope still tied to a ship’s mast.

The past is not lost. It’s just sleeping—2 kilometers beneath the surface of the Black Sea.

News

The Surgeon Stared in Horror as the Patient Flatlined—Until the Janitor Stepped Forward, Eyes Cold, and Spoke Five Words That Shattered Protocol, Saved a Life, and Left Doctors in Shock

“The Janitor Who Saved a Life: A Secret Surgeon’s Quiet Redemption” At St. Mary’s Hospital, the night shift is often…

Tied Up, Tortured, and Left to Die Alone in the Scorching Wilderness—She Gasped Her Last Plea for Help, and a Police Dog Heard It From Miles Away, Triggering a Race Against Death

“The Desert Didn’t Take Her—A K-9, a Cop, and a Second Chance” In the heart of the Sonoran desert, where…

“She Followed the Barking Puppy for Miles—When the Trees Opened, Her Heart Broke at What She Saw Lying in the Leaves” What began as a routine patrol ended with one of the most emotional rescues the department had ever witnessed.

“She Thought He Was Just Lost — Until the Puppy Led Her to a Scene That Broke Her” The first…

“Bloodied K9 Dog Crashes Into ER Carrying Unconscious Girl — What He Did After Dropping Her at the Nurses’ Feet Left Doctors in Total Silence” An act of bravery beyond training… or something deeper?

The Dog Who Stopped Time: How a Shepherd Became a Hero and Saved a Little Girl Imagine a hospital emergency…

Rihanna Stuns the World with Haunting Ozzy Osbourne Tribute — A Gothic Ballad So Powerful It Reportedly Made Sharon Osbourne Collapse in Tears and Sent Fans into Emotional Meltdown at Midnight Release

“Still Too Wild to Die”: Rihanna’s Soul-Shattering Tribute to Ozzy Osbourne Stuns the Music World Lights fade slow, but your…

“Ignored for Decades, This Humble Waiter Got the Shock of His Life When a Rolls-Royce Arrived with a Note That Read: ‘We Never Forgot You’” A simple act of kindness returned as a life-altering reward.

A Bowl of Soup in the Snow: The Forgotten Act That Changed Two Lives Forever The town had never known…

End of content

No more pages to load