The Secret Subway That Could Have Changed New York: Alfred Ely Beach’s Forgotten Pneumatic Dream

Long before the thunderous rattle of subway trains became part of New York City’s heartbeat, a quiet revolution hummed beneath its bustling streets—one powered not by electricity or diesel, but by air. In 1870, decades ahead of the city’s official subway system, inventor and publisher Alfred Ely Beach unveiled a secret project that dazzled the public, frightened the powerful, and hinted at a futuristic city that never quite came to be.

This is the story of the Beach Pneumatic Transit, a marvel of 19th-century ingenuity that promised to transform urban transportation—and might have, if not for politics and panic.

A Vision of Air-Powered Transit

Alfred Ely Beach, editor of Scientific American, was no ordinary inventor. A visionary with a flair for public spectacle, Beach believed that the future of urban transport lay beneath the ground. Cities were already becoming congested with horse-drawn carriages and omnibuses. Above-ground traffic was slow, smelly, and dangerous. Beach’s idea? A subway system that moved silently and smoothly—by air.

But in the 1860s, the idea of digging tunnels under New York’s streets was politically radioactive. Street-level transportation was controlled by powerful monopolies, notably the corrupt Tammany Hall political machine led by William “Boss” Tweed. These interests had no intention of letting a radical new idea disrupt their grip on the city’s infrastructure.

So Beach got clever.

A Tunnel Built in Secrecy

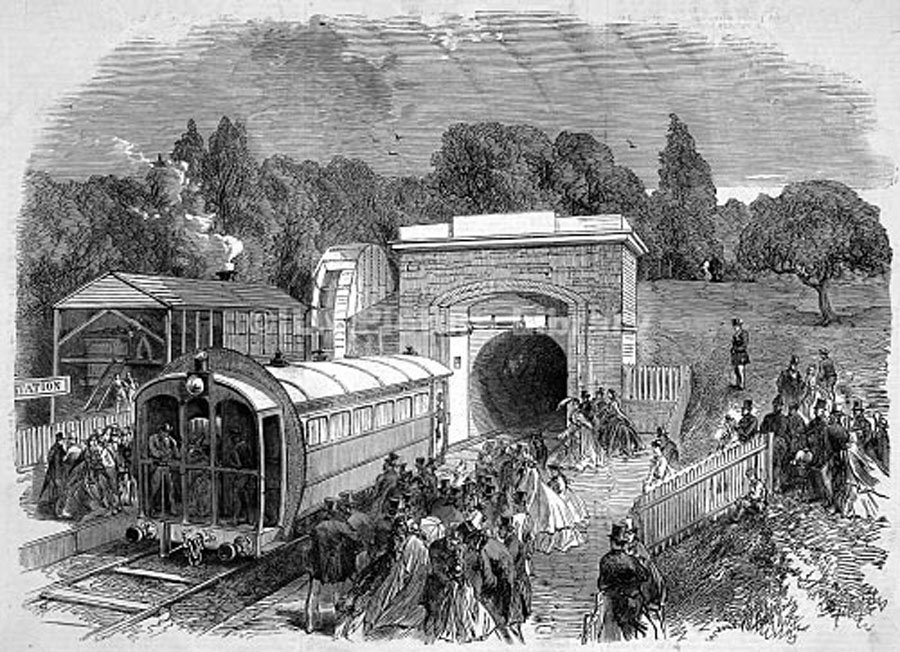

Instead of lobbying for a subway system outright, Beach submitted plans under the guise of constructing pneumatic mail tubes—a relatively innocuous and unthreatening innovation at the time. With vague city approvals secured, Beach and his crew began digging the tunnel in 1869. They worked primarily at night, using a special tunneling shield of Beach’s own design to avoid disrupting the surface above.

Incredibly, within less than a year, they had carved out a 300-foot tunnel running beneath Broadway, from Warren Street to Murray Street.

In February 1870, Beach opened the tunnel to the public, not as a mail system, but as New York’s first underground passenger railway.

A Victorian Wonderland Below the Streets

The Beach Pneumatic Transit wasn’t just a feat of engineering—it was an immersive experience.

The station, located in the basement of a department store, looked like a luxurious Victorian parlor. Passengers waiting to board the single-car train were treated to chandeliers, velvet chairs, intricate frescoes, a grand piano, and even a goldfish pond designed to soothe the nerves of anxious first-time subway riders.

The train car, a sleek, cigar-shaped vehicle, moved through the tunnel propelled by a massive 100-horsepower fan. Air pressure pushed the car forward and vacuum suction pulled it back—a simple yet revolutionary use of pneumatic technology.

The train could hold about 22 passengers and traveled at a modest speed. But that didn’t stop the public from swarming to ride it.

In its first year alone, over 400,000 people paid 25 cents each to experience this strange new world beneath the city.

Hope and Resistance

Beach’s dream was never limited to a 300-foot novelty ride. His ultimate goal was a full underground system stretching all the way to Central Park and beyond. He believed in the future of public transit—not just for efficiency, but as a way to unify the city socially and economically.

But political reality proved less idealistic.

Boss Tweed and his cronies, who profited from the surface-level streetcar lines, saw Beach’s project as a threat to their monopoly. They used every tool at their disposal—backroom deals, delayed permits, negative press—to block expansion.

For years, Beach fought on, lobbying the state legislature and courting investors. He even garnered some support in Albany. But just as his campaign gained momentum, disaster struck: the financial panic of 1873.

The economic downturn dried up investment capital. Combined with unrelenting political obstruction, it spelled the end of Beach’s dream.

A Forgotten Legacy

After the project was shut down, the tunnel was sealed and forgotten. Over the years, it was used for various odd purposes, including a wine cellar and a shooting gallery. When the city began building the real subway system in the early 20th century, Beach’s tunnel was rediscovered—and quietly destroyed during construction.

Today, no trace remains.

Yet Beach’s vision lives on in the DNA of modern New York.

Though his pneumatic system never expanded, Beach proved the viability of underground travel in a city notorious for political and engineering challenges. He did it without disrupting the surface, without taxpayer money, and without fanfare—until the day it opened.

What Could Have Been

It’s hard not to wonder what New York might look like today if Beach’s vision had been allowed to grow. A cleaner, quieter, more elegant subway? One perhaps less dependent on fossil fuels, less beholden to entrenched power?

His design was not just about transport—it was about imagination. About taking a bold leap toward the future, even when the odds were stacked against him.

Beach died in 1896, just six years before the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) opened the first official subway line. He never saw the realization of his dream—but perhaps he knew that one day, others would build on what he had started.

Epilogue: The Tunnel of Possibility

In the end, the Beach Pneumatic Transit wasn’t just a failed experiment—it was a symbol of what innovation can achieve when courage meets creativity.

It told the people of New York that the impossible was, in fact, quite possible. That even the most entrenched systems could be challenged. That sometimes, to build the future, you have to dig in secret—and hope the world is ready to follow.

Though hidden, sealed, and largely erased from memory, Beach’s tunnel remains one of the most romantic, radical, and remarkable chapters in the story of American innovation.

It was not merely a subway.

It was a dream beneath Broadway.

News

The Surgeon Stared in Horror as the Patient Flatlined—Until the Janitor Stepped Forward, Eyes Cold, and Spoke Five Words That Shattered Protocol, Saved a Life, and Left Doctors in Shock

“The Janitor Who Saved a Life: A Secret Surgeon’s Quiet Redemption” At St. Mary’s Hospital, the night shift is often…

Tied Up, Tortured, and Left to Die Alone in the Scorching Wilderness—She Gasped Her Last Plea for Help, and a Police Dog Heard It From Miles Away, Triggering a Race Against Death

“The Desert Didn’t Take Her—A K-9, a Cop, and a Second Chance” In the heart of the Sonoran desert, where…

“She Followed the Barking Puppy for Miles—When the Trees Opened, Her Heart Broke at What She Saw Lying in the Leaves” What began as a routine patrol ended with one of the most emotional rescues the department had ever witnessed.

“She Thought He Was Just Lost — Until the Puppy Led Her to a Scene That Broke Her” The first…

“Bloodied K9 Dog Crashes Into ER Carrying Unconscious Girl — What He Did After Dropping Her at the Nurses’ Feet Left Doctors in Total Silence” An act of bravery beyond training… or something deeper?

The Dog Who Stopped Time: How a Shepherd Became a Hero and Saved a Little Girl Imagine a hospital emergency…

Rihanna Stuns the World with Haunting Ozzy Osbourne Tribute — A Gothic Ballad So Powerful It Reportedly Made Sharon Osbourne Collapse in Tears and Sent Fans into Emotional Meltdown at Midnight Release

“Still Too Wild to Die”: Rihanna’s Soul-Shattering Tribute to Ozzy Osbourne Stuns the Music World Lights fade slow, but your…

“Ignored for Decades, This Humble Waiter Got the Shock of His Life When a Rolls-Royce Arrived with a Note That Read: ‘We Never Forgot You’” A simple act of kindness returned as a life-altering reward.

A Bowl of Soup in the Snow: The Forgotten Act That Changed Two Lives Forever The town had never known…

End of content

No more pages to load