The Pyramid Builders: New Discoveries Rewrite the History of Giza

For more than four millennia, the towering pyramids at Giza have inspired awe and mystery. The largest structures on Earth until the 20th century, they remain icons of ancient engineering brilliance and spiritual ambition. But while the colossal stones of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure have survived the centuries, the identity of those who built them has long been obscured by myth and speculation.

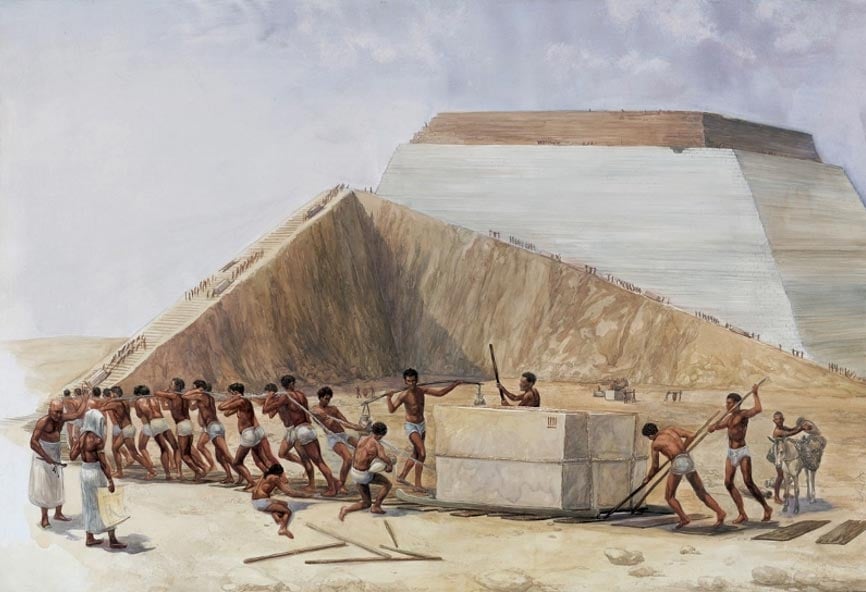

Were they slaves, as the ancient Greek historian Herodotus claimed? Were they foreign captives or peasants forced into labor under the lash of a whip? Or were they something else entirely — citizens of a highly organized, resource-rich society who dedicated their lives to a monumental cause?

Now, thanks to groundbreaking discoveries in the shadow of the pyramids, archaeologists are finally uncovering the truth — and it’s far more astonishing than fiction.

The Great Mystery of Construction

The three pyramids at Giza — built during Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty around 2600–2500 BCE — represent the zenith of pyramid construction in ancient Egypt. Khufu’s Great Pyramid alone is composed of more than 2.3 million limestone blocks, each weighing up to 15 tons. For centuries, no one knew how the Egyptians achieved such an extraordinary architectural feat without modern machinery.

But perhaps even more elusive was the question of who built them. Generations of scholars searched the sands for answers. While tombs of pharaohs and nobles offered glimpses into elite life, the lives of the workers remained hidden — until an accidental discovery in 1990 at Nazlet el-Samman, a Cairo suburb, changed everything.

Uncovering the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders

During routine construction work, a mechanical digger unearthed a large stone block buried beneath the sand. Archaeologists quickly took over the site and began to reveal the outlines of a vast ancient settlement. Excavations led by renowned Egyptologist Dr. Mark Lehner uncovered the remains of bakeries, workshops, storage areas, and workers’ dormitories. Bread molds, beer vats, and butchered bones were found in abundance.

Dubbed the “Lost City of the Pyramid Builders,” this massive complex was likely home to thousands of people — perhaps the very ones who constructed the pyramids.

Nearby, Dr. Zahi Hawass made an equally momentous discovery. Following a tip from a local guard, he uncovered a mudbrick wall and tombs nestled in the desert. These were not the tombs of pharaohs, but rather modest burials, untouched by looters, belonging to the very laborers who had lived and worked under the Egyptian sun.

A New Portrait Emerges

Over 600 graves were uncovered, spread over two levels. The lower, simpler tombs held ordinary workers, while the higher tier contained the remains of supervisors and artisans — those in charge of logistics, construction, and food preparation. Inscriptions on tombs included titles like “Inspector of the West Side of the Pyramid” and “Overseer of Sculptors,” confirming that these individuals were directly involved in pyramid construction.

The burial items were modest: pottery, tools, and symbolic artifacts. Yet their preservation offered an unprecedented look into everyday life. Archaeologists also discovered evidence of robust infrastructure to feed and house the workers, with thousands of animal bones — including prime cuts of young cattle — indicating a rich, protein-heavy diet.

This evidence contradicted the long-held belief that pyramid builders were slaves surviving on meager rations. Instead, they were well-fed and clearly valued.

The Power of DNA: Families in the Sand

Perhaps the most profound discovery came not from the tools or tombs, but from the bodies themselves. The skeletons revealed signs of hard labor — degenerative joint disease and broken bones that had healed — but they also told another story.

Initial analysis surprised scientists when they discovered a high proportion of women and children among the burials. Roughly half the adult skeletons were female, and over 20% were children, including infants. These weren’t seasonal laborers or enslaved populations — they were families.

To confirm the theory, Cairo University’s Medical School undertook DNA testing. Normally, ancient DNA extraction has a success rate of 40% due to degradation, but in this case, preserved in dry Egyptian sand, the success rate exceeded 80%. In several cases, genetic ties were confirmed between adults and children buried together, verifying they were blood relatives.

This was no slave camp — it was a community.

Slavery Theory Shattered

For decades, Western historians repeated Herodotus’ claim that the pyramids were built by slaves. Hollywood enshrined the image in films depicting ragged prisoners whipped beneath the hot sun. But modern archaeology has dismantled this myth brick by brick.

There is now no credible evidence to suggest mass slavery in pyramid construction. Instead, the emerging view is of a national project, involving skilled laborers, artisans, and seasonal workers — many of whom came from Egyptian provinces to serve for a few months or years before returning home. They were housed, fed, honored in death, and perhaps even revered in life.

Their dedication was not coerced — it was civic, even spiritual. The pyramid, after all, was not just a tomb. It was a bridge between Earth and the divine, and building it was part of a sacred duty to the living god-king.

What the Bones Reveal

Further study of the bones has revealed the incredible wear and tear of a physically intense life. Fractures, arthritis, and bone stress were common — especially in spinal columns and knees — consistent with hauling and shaping heavy stone. Yet in many cases, injuries had been treated. Bones had healed, indicating access to medical care and rest.

It wasn’t an easy life — but it was one with structure, purpose, and support.

Rewriting the History Books

These discoveries — the settlements, tombs, bones, and DNA — collectively paint a new and vivid picture of ancient Egypt. The pyramid builders were not nameless slaves, but respected workers, artisans, and families, living in an organized society capable of stunning engineering achievements.

As Dr. Lehner put it: “It brings the people back to life. It’s this information that allows us to reconstruct their world. This will be one of the most important chapters in the history of ancient Egypt.”

Conclusion: A Monument to a People

For over 4,500 years, the pyramids have stood in silence — monumental, mysterious, and misunderstood. But now, at last, we hear the voices of those who built them. Not in words, but in bones, bricks, and bakeries. They speak of family, of effort, of pride.

In a land where kings built for eternity, it is perhaps fitting that their builders, too, are finally remembered — not as slaves, but as the true architects of the ancient world’s greatest wonder.

News

Supreme Court Shockwave: John Roberts’ Racist Remark Toward Jasmine Crockett Met With a Historic Clapback That Left the Court, the Media, and America Speechless

“Truth on Trial”: How Jasmine Crockett Faced Down the Supreme Court and Changed American History It began as a routine…

Elizabeth Warren Tried to Publicly Humiliate Karoline Leavitt by Revoking Her Degree—But Got Exposed and Embarrassed on Live TV in a Stunning Political Reversal

“You Can’t Revoke the Truth”: How Karoline Leavitt Turned a Political Attack Into a National Reckoning It began as a…

Archaeologists Stunned as They Uncover Undisturbed Roman Vessel Loaded with Royal Treasures—A Lost Empire’s Secrets Finally Rise from the Depths of the Sea

Shipwreck of the Century: 4th-Century Roman Treasure Found in French River Could Rewrite Ancient History In a discovery hailed as…

“Explorers Discover Massive Underground Tunnel Network Covered in Ancient Engravings — What They Found Inside Left Them Speechless!” Archaeologists stumbled upon a labyrinth of tunnels hidden beneath the earth, with mysterious carvings along the walls. But it was what lay deep inside that left experts frozen in awe — forgotten symbols, chambers, and something no one expected to survive thousands of years untouched.

“Lost Underground: Explorers Stumble Upon Ancient Tunnel Network Hidden Beneath Villahermosa” In the unlikeliest of circumstances—on a routine trip to…

Basketball World STUNNED as Michael Jordan Declares Caitlin Clark ‘More Dangerous Than Any 2025 Olympian’ — Is She the New GOAT?” Michael Jordan’s bold comparison of Caitlin Clark to the entire 2025 Team USA roster has ignited wild debate. Calling her the most lethal scorer of her time, MJ left no doubt: the throne is hers to take. Has the greatest of all time just crowned his successor?

Basketball legend Michael Jordan sparked a social media frenzy by proclaiming Caitlin Clark a once-in-a-generation talent with the most versatile…

Karoline Leavitt’s SHOCKING Boycott Call Leaves ‘The View’ in Chaos — Internet Explodes: ‘Finally, Someone Had the Guts!

Karoline Leavitt Demands BOYC0TT of ‘THE VIEW’ LIVE On Air—Fans Erupt in Cheers, Flood Social Media With Praise: “FINALLY SOMEONE…

End of content

No more pages to load