The Forgotten Industrial Civilization of the Indus Valley: A 5,000-Year-Old Enigma

For centuries, the great civilizations of Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt dominated historical discourse, often seen as the earliest and most advanced cradles of human society. Yet, quietly nestled between the rivers of present-day Pakistan and northwest India, an equally astonishing civilization thrived — the Indus Valley Civilization. Once regarded as a peripheral culture or even a pale imitation of Mesopotamia, it is now emerging as one of the world’s earliest and most mysterious urban-industrial societies, rich in sophistication, trade, and technology.

From Cinderella to Titan: A Civilization Reconsidered

British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler famously referred to the Indus as “the Cinderella of civilizations,” suggesting it had long been overlooked — a forgotten sibling to the glittering kingdoms of the Middle East. But excavations beginning in the 20th century have radically shifted that narrative. With sprawling cities like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, covering hundreds of hectares, the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) reveals itself not as a faint echo of Sumer, but as a wholly distinct and powerful force that reached its peak around 2500 BCE.

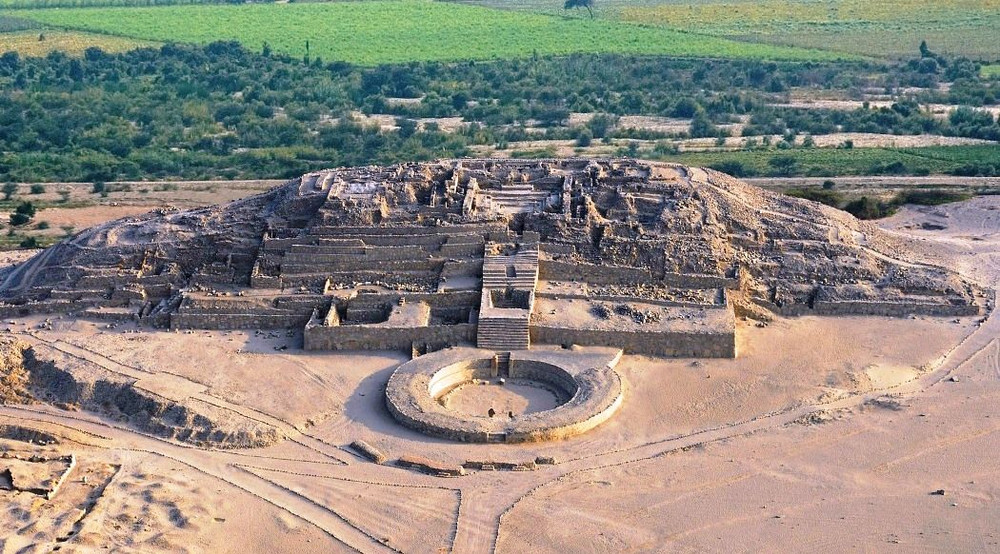

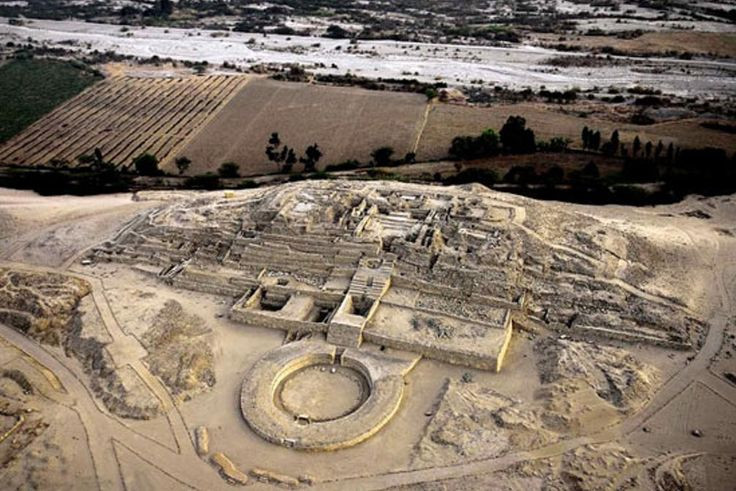

Mohenjo-Daro, in particular, stands as a marvel. Possibly the largest city of the ancient world by surface area, it featured a grid-based urban layout, advanced sewage systems, public granaries, and centralized planning—indications of an organized and perhaps even bureaucratic society. Unlike the towering temples of Mesopotamia, the Indus people appeared to invest more in civic infrastructure than monuments to kings or gods.

Rivers, Agriculture, and the Rise of Urban Industry

As with many ancient civilizations, rivers played a crucial role in the rise of the Indus society. The Indus and its tributaries once flowed across a vast, flat alluvial plain, providing fertile ground for crops and irrigation. This abundance allowed a surplus of food, which in turn supported non-agricultural classes — artisans, traders, and administrators.

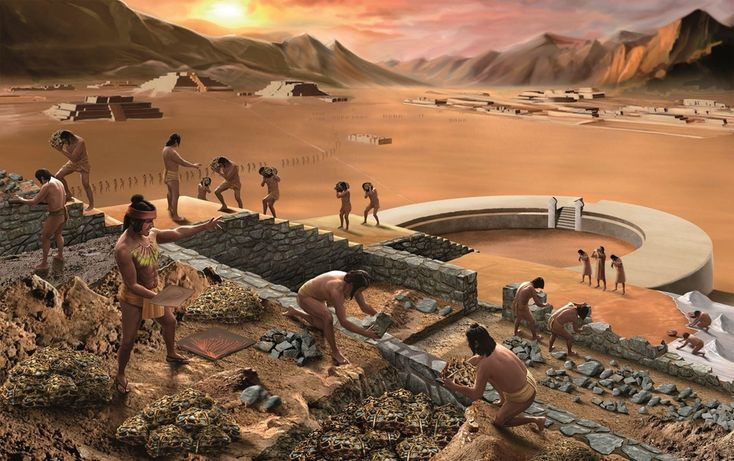

The economic engine of the Indus civilization was nothing short of revolutionary. In cities like Lothal and Dholavira, evidence has emerged of semi-industrial production of ceramics, bead-making, metallurgy, and possibly textiles. The famed red carnelian beads — large, polished, and perfectly shaped — are thought to have been exclusive to Indus artisans. These were traded across vast distances, even reaching the palaces of Mesopotamia. Some archaeologists believe the scale of production suggests the world’s first proto-industrial urban centers.

Though much of the evidence for such industry is perishable and lost to time, remnants — including standardized weights, seals, and kiln-fired bricks — suggest a remarkably uniform economic and cultural system. There are signs of regulated trade, central planning, and mass production far ahead of its time.

The Civilization That Wrote — But Left No Words

One of the most baffling aspects of the Indus Valley Civilization is its script. Thousands of inscriptions — mostly found on seals, pottery, and tablets — suggest a writing system was in active use. Yet, because these inscriptions are so brief and the writing medium was likely perishable (such as palm leaves or bark), no long texts have survived. Without a “Rosetta Stone” equivalent, the script remains undeciphered.

What is certain is that this was a literate and likely bureaucratic society, capable of record-keeping, administration, and trade documentation. The signs — sometimes compared to modern-day street signs or brand logos — hint at a complex language system. The presence of standard symbols across a vast area supports the notion of a connected civilization with shared norms and communication practices.

The silence of their written word continues to haunt historians and linguists alike. Until a longer text is found, or until a bilingual inscription is discovered, the full story of the Indus will remain tantalizingly out of reach.

Global Traders and Maritime Mariners

Long thought to be isolated, the Indus Valley people were, in fact, maritime traders of considerable reach. Archaeological finds of Indus goods in modern-day Oman, Bahrain, and Mesopotamia, alongside Sumerian texts referencing trade with a distant land called Meluhha (likely the Indus region), confirm a wide and complex trade network.

A cuneiform inscription from the Akkadian king Sargon (c. 2300 BCE) describes ships from Dilmun (modern-day Bahrain), Magan (Oman), and Meluhha arriving at his capital. The goods traded included precious carnelian, ivory, timber, textiles, and likely spices. Textiles, though perishable, are believed to have been one of the civilization’s most important exports.

What’s even more fascinating is the recorded existence of a translator from Meluhha, mentioned in a Mesopotamian tablet. This hints at direct contact between cultures and a multilingual world where translation and diplomacy were essential — a reminder that globalization is far from a modern concept.

Decline Without Collapse

Unlike the sudden collapses seen in other ancient cultures, the decline of the Indus civilization was gradual and complex. By around 1900 BCE, the great cities began to be abandoned. The reason was not necessarily conquest or catastrophe, but a process scholars now call “regionalization.” This involved the breakdown of the centralized system into smaller, local cultures that continued many Indus traditions in more rural, less archaeologically visible forms.

Shifting river patterns, environmental changes, and perhaps economic strain from maintaining large urban centers likely contributed to the decline. But the people themselves did not vanish. Instead, they adapted, migrated, and integrated — leaving behind cities of brick and signs, and entering the realm of oral tradition and rural lifeways.

Legacy of a Silent Giant

Today, the Indus Valley Civilization challenges our perceptions of what a “great” ancient society looks like. Without kings, without war monuments, and without deciphered texts, it has long been treated as mysterious and marginal. But its scale, urban planning, industrial capacity, and transcontinental trade place it firmly among the most advanced civilizations of the ancient world.

Perhaps most poignantly, the Indus Valley teaches us that history isn’t always loud. Sometimes, the most sophisticated achievements leave only quiet footprints — in clay seals, buried bricks, and broken beads — waiting for modern minds to recognize their echo.

Until we learn to read their words, the people of the Indus will remain our most eloquent silent ancestors — builders of a forgotten industrial age that once lit up the ancient world.

News

The Surgeon Stared in Horror as the Patient Flatlined—Until the Janitor Stepped Forward, Eyes Cold, and Spoke Five Words That Shattered Protocol, Saved a Life, and Left Doctors in Shock

“The Janitor Who Saved a Life: A Secret Surgeon’s Quiet Redemption” At St. Mary’s Hospital, the night shift is often…

Tied Up, Tortured, and Left to Die Alone in the Scorching Wilderness—She Gasped Her Last Plea for Help, and a Police Dog Heard It From Miles Away, Triggering a Race Against Death

“The Desert Didn’t Take Her—A K-9, a Cop, and a Second Chance” In the heart of the Sonoran desert, where…

“She Followed the Barking Puppy for Miles—When the Trees Opened, Her Heart Broke at What She Saw Lying in the Leaves” What began as a routine patrol ended with one of the most emotional rescues the department had ever witnessed.

“She Thought He Was Just Lost — Until the Puppy Led Her to a Scene That Broke Her” The first…

“Bloodied K9 Dog Crashes Into ER Carrying Unconscious Girl — What He Did After Dropping Her at the Nurses’ Feet Left Doctors in Total Silence” An act of bravery beyond training… or something deeper?

The Dog Who Stopped Time: How a Shepherd Became a Hero and Saved a Little Girl Imagine a hospital emergency…

Rihanna Stuns the World with Haunting Ozzy Osbourne Tribute — A Gothic Ballad So Powerful It Reportedly Made Sharon Osbourne Collapse in Tears and Sent Fans into Emotional Meltdown at Midnight Release

“Still Too Wild to Die”: Rihanna’s Soul-Shattering Tribute to Ozzy Osbourne Stuns the Music World Lights fade slow, but your…

“Ignored for Decades, This Humble Waiter Got the Shock of His Life When a Rolls-Royce Arrived with a Note That Read: ‘We Never Forgot You’” A simple act of kindness returned as a life-altering reward.

A Bowl of Soup in the Snow: The Forgotten Act That Changed Two Lives Forever The town had never known…

End of content

No more pages to load