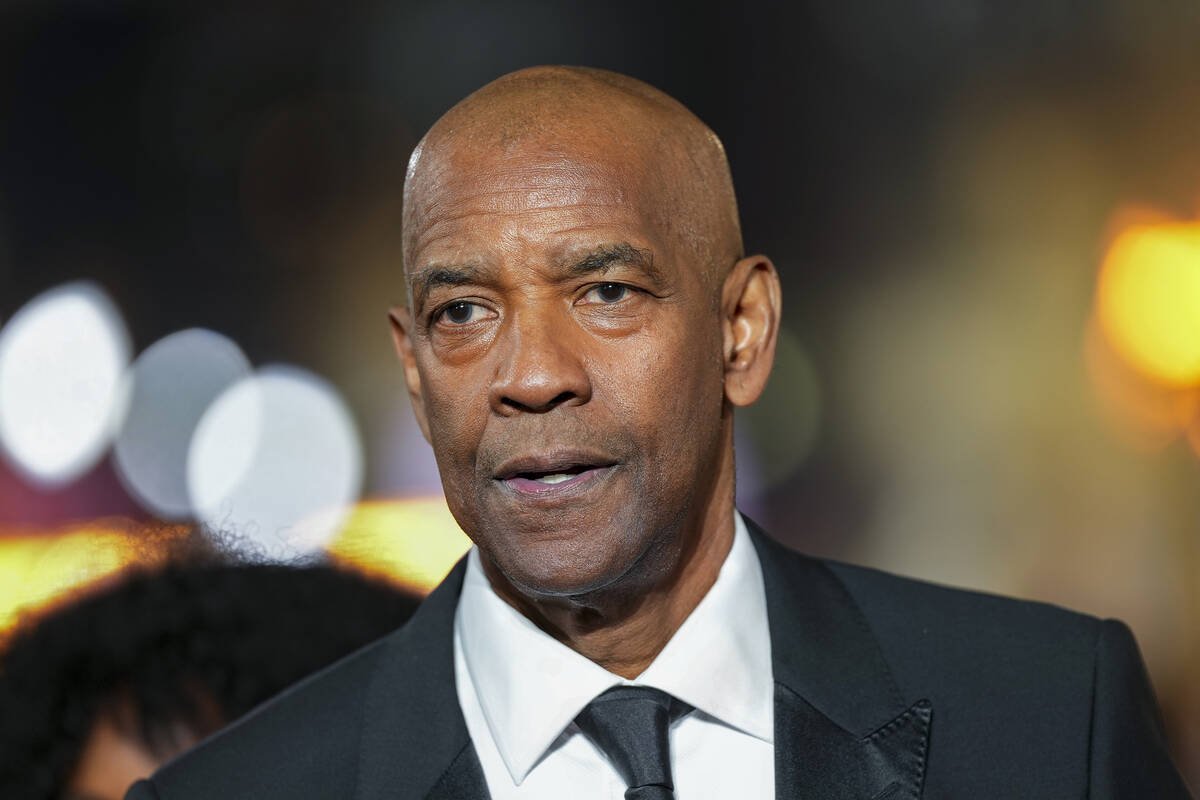

“Your Time Has Not Expired”: The Day Denzel Washington Stunned the Supreme Court

It began like a scene from a legal drama—but it wasn’t fiction. Denzel Washington stood tall and composed at the lectern in Courtroom 3 of the U.S. Supreme Court, his tailored navy suit stark against the backdrop of marble columns. The room buzzed with a strange energy, somewhere between skepticism and disbelief. He wasn’t there to act. He was there to argue.

Moments earlier, Chief Justice John Roberts had interrupted Washington’s opening statement with a challenge that cut deeper than any legal objection:

“Mr. Washington, I find it difficult to believe that someone from your background fully understands the constitutional implications of your position.”

Gasps. Glances. Scribbles. It was a moment designed to rattle a novice—especially one with a Hollywood résumé rather than a judicial pedigree. But Washington, calm as ever, looked Roberts in the eye and responded not with indignation, but with law.

The actor had spent five years quietly earning his JD from Howard University School of Law while continuing his film career. Few knew. Fewer still believed he’d ever set foot in a courtroom, let alone the highest one in the land. But when he filed a 40-page amicus brief in Henderson v. Department of Justice, a case about the government’s controversial use of civil forfeiture laws, the Court—perhaps intrigued, perhaps amused—granted him 10 minutes of oral argument.

Most expected a PR stunt. What they got was a constitutional reckoning.

From Movie Star to Legal Star

Henderson was not a routine property case. It involved the seizure of a Black community center and neighboring homes in Philadelphia—taken by the government without charging the owners with any crime, based solely on a single drug sale that occurred nearby. Washington’s brief argued that such seizures violated the original meaning of the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause.

It was a radical argument, steeped in historical sources, founding-era court cases, and a textualist theory that placed him squarely in the company of serious legal minds. But to Chief Justice Roberts, a Harvard Law man and longtime skeptic of judicial showmanship, it looked like celebrity dabbling.

That skepticism didn’t last long.

The Cross-Examination Backfires

Washington opened with poise, articulating his thesis clearly:

“The Fifth Amendment’s requirement of ‘just compensation’ also presumes a legitimate public use and basic procedural fairness. Without those, it’s not just unconstitutional—it’s un-American.”

Roberts interrupted just 40 seconds in, violating usual decorum.

“Your brief overlooks two centuries of settled doctrine,” he said pointedly. “I find it difficult to believe that someone from your background fully understands the implications.”

The air turned electric. Even Justice Sotomayor shifted uneasily. Elena Kagan frowned. But Washington remained unshaken.

“With respect, Chief Justice, I believe my argument aligns with Justice Thomas’s historical concurrence in Timbs v. Indiana. If it pleases the Court, perhaps we could examine the textual and historical evidence together.”

Then he opened a battered pocket Constitution, along with hand-marked transcripts of 18th- and 19th-century court cases. He wasn’t here to perform. He was here to teach.

A Legal Mind, Revealed

What followed was a slow, stunning shift in courtroom dynamics. Roberts pressed Washington on The Palmyra (1827), a landmark case used to justify government seizure of property. Washington didn’t blink. He cited the case—page 23 of his brief—and clarified that it involved piracy and maritime law, where the government lacked personal jurisdiction. It was never meant to justify domestic seizures without criminal convictions.

Justice Alito interjected with Bennis v. Michigan, where a woman’s car was seized after her husband used it for illegal activity without her knowledge. “Justice Alito, I believe Bennis was wrongly decided,” Washington said, citing dissents from both Justice Thomas and Justice Ginsburg.

By now, Roberts had stopped trying to expose gaps in Washington’s reasoning and was engaging seriously. “You cite obscure state cases that most scholars don’t mention. How can we trust they represent mainstream doctrine?”

Washington smiled. “I’m glad you asked.” He then recited holdings from eight early state supreme courts showing uniform resistance to land-based civil forfeiture. Kagan asked if he had help from historians.

“No, Your Honor. I conducted the research myself at Howard. And in the years since graduation.”

The Justices Begin to Shift

As Washington spoke, justices leaned forward. Notes were taken. Even Clarence Thomas, normally silent, watched intently. When asked for a proposed legal standard, Washington offered a crisp three-part test:

A substantial connection to criminal activity.

Either a conviction or clear evidence the owner knowingly permitted wrongdoing.

A demonstrable public use—not revenue generation—for any forfeiture.

It was elegant, historically grounded, and practical. The courtroom had transformed. Roberts no longer saw a celebrity. He saw a constitutional thinker.

A Legal Legacy Begins

When Washington’s time expired, the traditional call of “Your time has expired” never came. Silence reigned. Then, from the Chief Justice:

“Thank you, Mr. Washington. Your argument has been exceptionally informative.”

That moment—those few understated words—carried the weight of an apology, a recalibration, a national rethinking of who belongs in America’s highest courtrooms.

Washington returned to his seat. The government’s lawyer rose—visibly shaken. The balance of the case had shifted. The Court had heard not a movie star, but a scholar.

The Decision That Changed Everything

Six weeks later, the Court issued its opinion: 7–2 for the petitioners. The government’s seizure of the Philadelphia properties was ruled unconstitutional. Roberts himself wrote the majority, quoting Washington’s brief four times, and adopting his three-part test nearly verbatim. Justice Thomas concurred, calling for a full rethinking of modern civil forfeiture. Justice Sotomayor highlighted the disproportionate impact on communities of color.

In a final paragraph that stunned court watchers, Roberts wrote:

“This case reminds us that legal wisdom can come from unexpected sources… The Court benefited greatly from the thorough advocacy and historical insights provided by all who participated in this important case.”

A Modern Parable

Washington’s argument has since been assigned in law schools. Applications from underrepresented minorities surged. The American Bar Association invited him to keynote its annual conference.

He created the Washington Justice Initiative, a nonprofit aiding those affected by property seizures. At Georgetown, he joined Roberts on stage to discuss civic education. The Chief Justice, in an unusual moment of candor, said:

“Mr. Washington taught me a valuable lesson. Never confuse celebrity with capability.”

Washington, as always, was gracious.

“In law as in acting, preparation is everything. And justice must be blind—not to identity, but to assumption.”

That day in court will be studied for generations—not just for its impact on constitutional law, but for its deeper truth: brilliance does not always wear a robe. Sometimes, it wears a suit, carries a Constitution, and refuses to flinch.

News

Meryl Streep abruptly walked off the set of ‘The View’ after a shocking on-air clash with Whoopi Goldberg. Tension escalated so fast that producers were caught off guard. Was this just a heated disagreement — or something much deeper between two Hollywood legends? Watch the chaos unfold.

The Day Hollywood Collided: The Live TV Confrontation Between Meryl Streep and Whoopi Goldberg In the ever-unpredictable world of live…

You Won’t Believe What Jasmine Crockett Just Said on Live TV — She Pulled Out Documents, Named Names, and Left Mike Johnson Stunned and Speechless in the Middle of a Heated Debate Everyone’s Talking About Now.

“Class Is Now in Session”: Jasmine Crockett’s Constitutional Takedown of Speaker Mike Johnson In a political world often dominated by…

Pam Bondi made one bold move on air, targeting Jasmine Crockett in front of millions—but she didn’t realize she was walking straight into a trap. What happened next not only embarrassed her publicly but also triggered calls for her resignation.

Pam Bondi’s Congressional Showdown Redefines Oversight In a stunning and unexpected turn of events, a congressional oversight hearing that had…

Tension erupts on The View as Denzel Washington calls out Joy Behar — seconds later, he walks out live on-air, leaving the audience in disbelief.

When Legends Collide: The Day Denzel Washington Took a Stand on “The View” In the world of Hollywood, few names…

When Oprah asked Karoline Leavitt a question meant to shake her faith on national TV, no one expected the 25-year-old to answer the way she did — calm, powerful, and unforgettable. What happened next left Oprah speechless and the internet on fire.

Faith, Truth, and Cultural Power: How Karoline Leavitt Shifted the National Conversation on Oprah’s Stage In a world saturated with…

Jasmine Crockett delivers a jaw-dropping clapback that leaves Josh Hawley completely stunned – cameras capture the moment he freezes on live TV after failing to respond. You won’t believe what she said that shut him down instantly!

How Jasmine Crockett Silenced Josh Hawley: A Masterclass in Political Rhetoric and Moral Clarity In what many are calling one…

End of content

No more pages to load