And why the lawsuits between Baldoni and Lively are particularly complex and hard to follow.

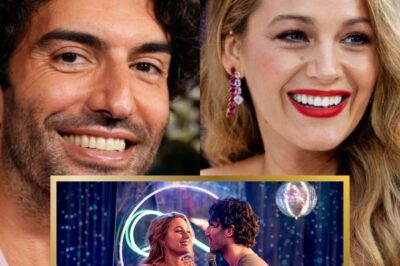

As the mudslinging and legal cases continue to escalate between actors Blake Lively and Justin Baldoni, it’s hard to say if these celebrities are heading toward mutually assured destruction — or new levels of fame and notoriety.

A trial date of March 2026 has been announced for Lively’s initial case against Baldoni and his team, following the pair’s summer rom-com “It Ends with Us,” which both actors starred in and which Baldoni also produced and directed. A New York federal judge said in a pretrial hearing that date may be moved up should their disputes continue to be “litigated in the press.”

What we’re learning in the era of digital evidence is that even when there’s a video of an event, two sides will interpret it differently.

In many ways, the very public conflict calls to mind the messy, much-discussed 2022 Johnny Depp and Amber Heard trial as a Hollywood cautionary tale. Before the Depp-Heard case the then-conventional wisdom was that even if movie stars win in court, they risk losing their brand in messy courtroom battles.

There are differences between the feuds. Depp and Heard were married, for one. And while the Depp-Heard libel trial got the kind of television coverage comparable to the O.J. Simpson murder trial, we don’t know what this one will bring. Similarly to Depp and Heard, the highly publicized legal battles of Lively, her husband and Hollywood mogul Ryan Reynolds, and Baldoni might leave them all more famous than they were before it started. The question is, at what price?

Lively fired the opening salvo in the legal skirmish when she filed a workplace complaint against Baldoni, alleging sexual harassment and an overall toxic work environment during the filming of “It Ends With Us.” Among other things, Lively claimed Baldoni engaged in inappropriate conduct on set, including discussing his sex life and improvising a kiss into a scene without her consent. She also alleged Baldoni’s publicists carried out a smear campaign attacking her during the press tour for their film, damaging her career and reputation. (Baldoni’s attorney responded to the allegations saying they are “completely false, outrageous and intentionally salacious.”) Legally speaking, the complaint was a potentially smart tactical move by Lively’s legal team. By filing with the California Civil Rights Department, she was able to make allegations without having to actually file those allegations in a court.

But Baldoni’s legal team quickly fired back. Baldoni promptly filed a counter suit against Lively, Reynolds and her publicist for $400 million — claiming defamation, civil extortion and that his named defendants embarked on a campaign to ruin his career. Separately, Baldoni is also suing The New York Times for $250 million over what he says amounted to a smear campaign in its coverage of Lively’s lawsuit, by publishing what he says are cherry-picked, incomplete snippets of evidence in a Dec. 21 article on her filing against Baldoni.

Of these, the lawsuit against the Times may have the best shot. Not because Baldoni’s case is particularly strong against it, but because the lawsuits between Baldoni, Lively and Reynolds are particularly muddy and hard to follow. Each of their stories varies wildly from the other’s. Sure, they have plenty of text messages, voice memos and even footage to use as evidence. But what we’re learning in the era of digital evidence is that even when there’s a video of an event, two sides will interpret it differently. Take the uncomfortably long Baldoni voice memo that recently emerged. I’m pretty sure that Baldoni listened to that voice memo and thought: “See? Everyone is going to hear this and know I’m right!” And I’m equally sure that Lively listened to the same voice memo and thought, “See? Everyone is going to hear this and know I’m right.”

This is a universal truth of civil litigation: Everyone is wired to believe they are in the right, even in the face of overwhelming evidence that they are in the wrong.

If any of these Baldoni v. Lively cases go to trial, at best, they will be coin flips. That’s what juries have to do when they are confronted with two wildly different stories: pick one. That’s the best case scenario.

It’s equally likely that a jury will be utterly confused by all this behind-the-scenes movie set culture that is totally alien to most regular working folks. Meaning that no matter who wins in court, it’s possible that the public’s verdict will ultimately be that everyone involved in this case is entitled and unrelatable. In the meantime, there’s plenty of time for more drama to unfold between the various parties while we wait for it to go to trial

News

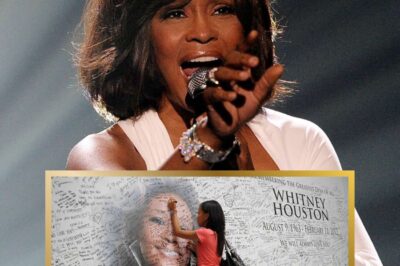

Whitney Houston’s Death: The Details Behind Her Sudden Passing 13 Years Ago!

Whitney Houston was just 48 years old when she died at a Beverly Hills hotel in February 2012 Photo: Kevork…

These Rare ‘Friends’ Throwback Photos Will Make You Feel All the Nostalgia!

There is never a bad time to enjoy throwback photos of the Friends cast! Take a walk down memory lane with your…

17 Throwback Photos of Beautiful Birthday Girl and Friend Jennifer Aniston!

Truth be told, she’s always looked fantastic. Revisit Jennifer Aniston’s decades of iconic style in honor of her 56th birthday…

Courteney Cox’s Heartfelt Birthday Message to Jennifer Aniston Will Melt Your Heart!

“I feel so lucky to be growing up with you,” Cox told her fellow ‘Friends’ alum in a sweet birthday…

BREAKING NEWS: Justin Baldoni heats up legal battle against Blake Lively with new claims!

Days before court hearing, Justin Baldoni drops bombshell claims about Blake Lively feud Justin Baldoni heats up legal battle against…

Blake Lively’s Feelings On Taylor Swift’s Super Bowl ‘Snub’ Revealed Amid The Actress’s Legal Woes

Blake Lively‘s friendship with Taylor Swift seems to be heading for the rocks after the pop star snubbed her from her Super…

End of content

No more pages to load